|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Progressive Miners of America and the 1930's Illinois Mine War

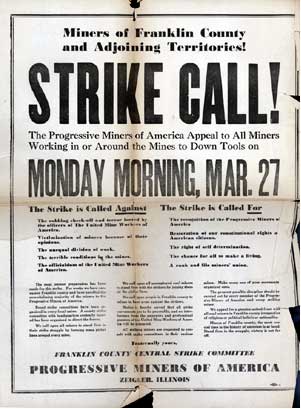

In March 1932, the wage contract between Illinois coal operators and United Mine Workers District 12 miners expired. With coal demand and prices waning, operators sought to substantially reduce miner’s pay. District leadership negotiated a reduction from $6.10 per day to $5.00. However, the contract was subject to rank and file approval. A vote was held in July 1932, and the union membership soundly rejected the agreement. District President John Walker called on UMWA President John L. Lewis to come to Illinois to convince miners accept the deal. However, when Lewis or Walker spoke publicly in support of the new agreement, they were often met with catcalls and organized protests from the rank and file. On August 6, a new election was held. Before the tallies could be made public, the ballots were stolen. Instead of retrieving the ballots or holding a new election, John L. Lewis immediately declared an emergency and imposed the $5.00 per day agreement on the workers. (Later, the license plate number of the robbery get-away car was traced to District 12 Vice President, Fox Hughes.) In protest, miners organized mass pickets in a number of coal towns in Central Illinois. On August 24, a mass march was organized to win the support of workers in the Southern part of the state. The huge caravan was met by scores of deputies and thugs at Mulkeytown, Illinois. Vehicles were upended and workers were shot at and beaten. Eight days later, delegates representing tens of thousands of miners assembled in Gillespie, Illinois. They voted to break from the UMWA and form a new union, the Progressive Miners of America (PMA). The PMA was more than simply a rival to the UMWA. Rejecting Lewis' autocracy, the new union adopted democratic policies and instituted measures to ensure that their leaders would be held accountable to the membership.

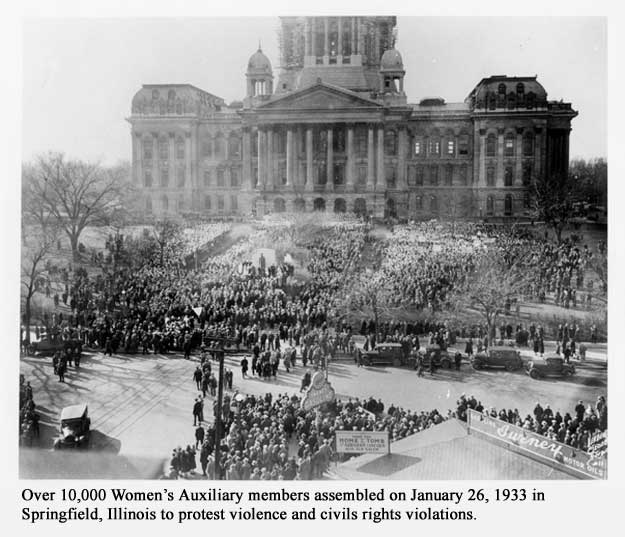

However, the Governor turned a deaf ear to the plight of the dissident unionists. As violence continued to mark the subsequent years, the stance of state and federal government tilted increasingly in support of the UMWA. The PMA didn't fair much better in the federal labor bureaucracy either. While passage of the Wagner Act is commonly celebrated as a victory for organized labor, the law was unevenly enforced. The rights of the PMA to speak, assemble and organize inside and outside of Illinois were frequently violated. Repeated demands for state-wide recognition elections by the union were also rejected by the National Labor Board. This was hardly surprising given Lewis held a seat on the board. Law Professor Jim Pope writes, "By early 1934, exit from the UMW was no longer a viable option for union miners. With the cooperation of employers and courts, the UMW had used its quasi-governmental position to withering effect against the alternative unions."3

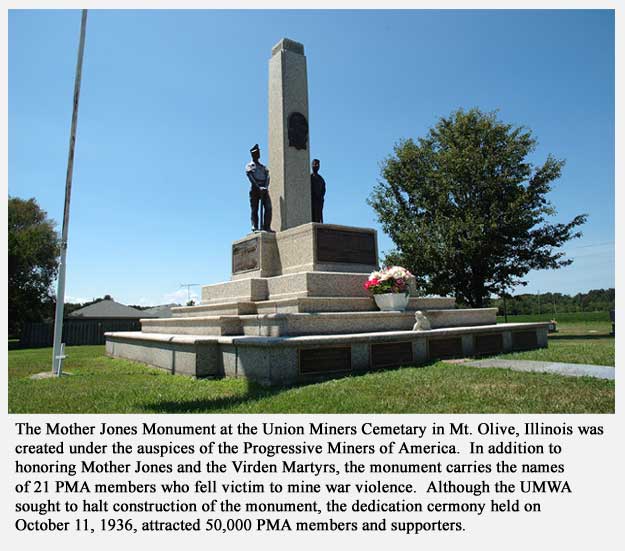

While the Progressives were frequently blamed for the violence, the UMWA and the major coal operators benefited from its results. The shootings and bombings provided the impetus for the intervention of the state militia and the imposition of martial law in several key mining communities. With the military in control of these areas, Progressive strikes were broken as scabs worked under the protection of the state. The PMA suffered a crucial blow in 1937 when 39 members were indicted in federal court on anti-racketeering charges. Although the defense provided compelling evidence of UMWA collusion with the Peabody Coal Company, the jury returned guilty verdicts for the accused. Subsequently, 34 received federal prison sentences, many serving time in Leavenworth, Kansas.

The union was also torn internally. Conservative leaders resisted the efforts of radicals to expand the alternative formation of the union. Red-baiting was adopted to attack and discredit left-leaning members. When the PMA formerly affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1937, radicals regarded it as a betrayal, believing the AFL a regressive organization, hostile to the interests of unskilled labor. While the union formally continued to exist until 1999, its possibility to offer mine workers a genuine alternative dissolved decades earlier. Paired against the combined forces of the UMWA, the state and federal government, and the coal operators, the Progressives were hindered at every turn. Notes 1Staughton Lynd, “We Are All Leaders”: The Alternative Unionism of the Early 1930’s, (University of Illinois Press, 1996, p. 3) 2Caroline Waldron Merithew, “We Were Not Ladies” Gender, Class, and a Women’s Auxiliary’s Battle for Mining Unionism, Journal of Women’s History, Vol. 18 No. 2, 2006, p 66. 3Jim Pope, The Western Pennsylvania Coal Strike of 1933, Part II: Lawmaking from Above and the Demise of Democracy in the United Mine Workers, Labor History, Vol. 44, No. 2, 2003, p. 259 |

||

|